By Jeff Kelly Lowenstein

It’s been a rough couple of weeks in the United States and the world.

The killing of Renee Good by ICE agent Jonathan Ross in Minneapolis.

The Trump Administration’s announcement that it had launched a criminal investigation into Fed Chairman Jerome Powell.

The country’s return to 19th century gunboat diplomacy as U.S. forces carried out a military strike that led to the capture of incumbent Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores.

And Trump’s statement that the United States’ path to owning Greenland will come “the easy way” or “the hard way”.

An incomplete list, these actions represent what some have called a polycrisis that can lead to people feeling overwhelmed and despairing about the future.

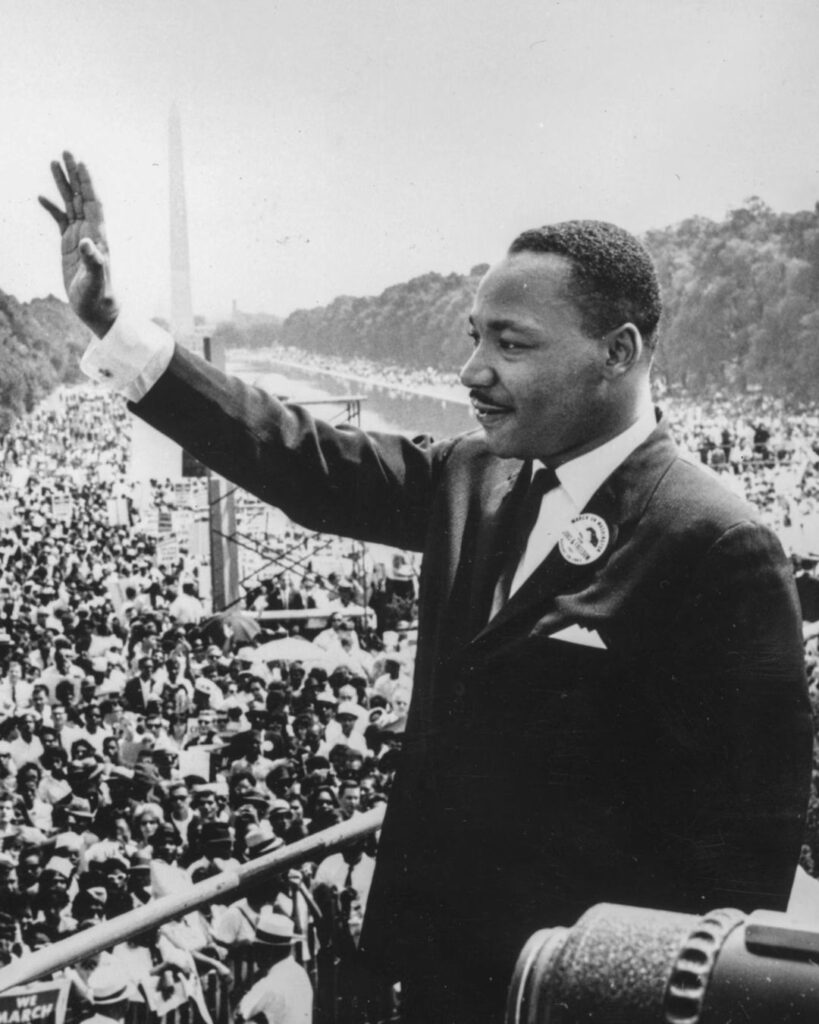

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose birthday the United States marks as a national holiday today, was familiar with those feelings, particularly in the last 18 months of his life. How he managed to not let them stop him from continuing to expand and pursue his prophetic vision can be a source of strength and inspiration for us now.

King first came to public consciousness during the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott that was sparked by NAACP secretary Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat and move to the back of the segregated bus. (More on this in the second part of this series.) A relative newcomer to the city, King was initially tapped by black leaders in Montgomery to head the newly formed Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) precisely because he was not a well-known figure and thus could be less divisive than some more entrenched black leaders and more palatable to the white establishment.

King’s actions met the moment. In the association’s initial meeting, he assured the energized crowd in the packed Holt Street Baptist Church of the righteousness of their case.

“I want it to be known that we’re going to work with grim and bold determination to gain justice on the buses in this city,” he said in a slow cadence that gained volume and strength as he repeated his mantra. “And we are not wrong.… If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong.”

Then 26 years old, King assumed the mantle of leadership and the heightened risk that came with it. In a major test of the boycott’s commitment to nonviolent protest, his house with his family, including a newborn baby, was bombed on January 30, 1956. An angry crowd gathered at the home, ready to carry out vengeance on those who had attacked their leader and his family. He urged them to respond in a nonviolent fashion.

If you have weapons, take them home; if you do not have them, please do not seek them,” he pleaded. “We must meet violence with nonviolence…We are not hurt, and remember, if anything happens to me there will be others to take my place.”

The last part of his statement reflected the death threats that became a daily staple for King during the last third of his life. While speaking at Mount Pisgah Missionary Baptist Church in Chicago in 1967, he recounted the story of a threat that came in the form of a call in Montgomery that required divine inspiration.

It came around midnight at the end of a long day, he said. The message was simple and laced with a racial epithet: We’re tired of you and what you’re doing. Get out of town in three days, or we’ll kill you and blow up your house.

Although King was accustomed to shaking them off these threats, this one jolted him. Unable to return to sleep, he eventually went into his kitchen for a cup of coffee to calm his nerves. He started thinking about the theology he had studied for years, about his beautiful little girl who had just been born, and about his dedicated and loving wife. King then thought of reaching out to his father, a well-respected preacher, but he was 175 miles away in Atlanta. He even considered contacting his mother.

Nothing worked.

He realized he needed to call on his profound belief and to ask for help from the god in which he believed so fervently. With the crowd clapping and calling out, King said that he bowed down over the cup of coffee and uttered the following prayer:

“Lord, I’m down here trying to do what’s right. (Yes) I think I’m right; I think the cause that we represent is right. (Yes) But Lord, I must confess that I’m weak now; I’m faltering; I’m losing my courage. (Yes)”

King’s voice rose as he told the crowd that he heard a voice instructing him:“Martin Luther, (Yes) stand up for righteousness, (Yes) stand up for justice, (Yes) stand up for truth. (Yes) And lo I will be with you, (Yes) even until the end of the world.”

It rose even further as he roared his belief:

“And I’ll tell you, I’ve seen the lightning flash. I’ve heard the thunder roll. I felt sin- breakers dashing, trying to conquer my soul. But I heard the voice of Jesus saying still to fight on. He promised never to leave me, never to leave me alone. No, never alone.”

Fortified by the message that he would always have G-d’s support with him, King found the strength to continue in Montgomery, Albany, Birmingham, Selma and other locations throughout the rest of his life.

His woes mounted during his final 18 months. Derided by increasingly radical young activists like Stokely Carmichael, he also lost the support of the Johnson White House due to having spoken out against the Vietnam War in a speech at Riverside Church exactly one year before his assassination. His Chicago campaign to eliminate slum housing was widely seen at the time as unsuccessful, while some in SCLC found the goals of his Poor People’s Campaign too amorphous. Indeed, Harlem Congressman Adam Clayton Powell mocked his former ally as “Martin Loser King” shortly before his death.

These compounding challenges took place while his conviction that he would not live a full life became increasingly firm. “This is what’s going to happen to me,” King told his wife, Coretta, after JFK was killed in 1963, according to the BBC. “I keep telling you, this is a sick society.”

The BBC also noted that King had been in a fragile state in the months leading up to his assassination in Memphis. That doubt – that despair, even – was revealed in a Virginia hotel room, seven months before he died. After a meeting with colleagues, King was drinking alone when he woke them up, shouting.

“I don’t want to do this anymore!” he yelled, according to the BBC. “I want to go back to my little church!”

King did not return to his church, but he did persist in fighting for justice until the day before his death, when he delivered the address commonly known as the “I have been to the mountaintop”. “I may not get there with you,” he declared memorably to the crowd of 2,000 people gathered in the Mason Temple in Memphis. “But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

A bullet shot by James Earl Ray tore through King’s right cheek the next day just after 6:00 p.m. as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, shattering his jaw and several vertebrae, severing his spinal cord, and killing him.

On the day we mark the 97th anniversary of Dr. King’s birth, we, too, can feel discouraged. Yet we can learn at least as much from his struggles with doubt as from his soaring rhetoric and eloquent phrases. We can draw from King’s example of how he managed, despite feeling beleaguered and attacked on many sides, to rely on his faith and continue fighting for justice. And, whether we are people of faith or not, we can find our own sources of inner strength to meet the many challenges we encounter with the same resolve King exhibited until he drew the final breath of his remarkable life.

Jeff Kelly Lowenstein is the founder and executive director of the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ) and an associate professor of journalism at Grand Valley State University.

NOTE: A section of this article previously appeared on Jeff Kelly Lowenstein’s blog.